“Why Now, Why This, Why You”: How a VC Filters AI & Hardware Startups

VC associate Michelle Wang shares how she evaluates early-stage AI and hardware projects. What signals make her lean in, why founder motivation matters more than pitch decks, and what mistakes foreign founders still make when approaching Chinese investors.

After years working across Africa and the Middle East, Michelle returned to China and now moves between Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen, and Silicon Valley. In early-stage investing, she pays close attention to founder clarity, team conviction, and whether a product is built for short-term buzz or long-term traction.

1. When an AI project first lands on your desk, what are the fastest reasons you decide not to spend more time on it?

To be honest, I rarely pass on a project purely out of instinct. Most of the time, I prefer to speak with the founders or the founding team before making any decision.

Many AI startups today have pitch decks that are quite abstract. They’re filled with new concepts and technical jargon, and sometimes investors don’t fully understand what the team is actually building just from the slides. Misunderstandings often come from storytelling rather than from the product itself.

So I usually schedule a 45-minute to one-hour conversation with the founders to understand clearly what they’re building and how they think about the product.

After that conversation, the key factor for me becomes the founding team, especially the founder’s motivation.

I care deeply about why you’re in this business. Why did you decide to build this product? Entrepreneurship is abstract and extremely difficult. It requires conviction and resilience. If someone is building a company because their Stanford roommates raised money from a16z, or because they want fame, reputation, or to become a KOL, that’s when I would pass.

There are simply too many hardships in entrepreneurship. If the motivation is superficial, it won’t sustain the company.

2. At the early stage, how would you rank the problem being solved, the founding team, and the technology or solution and why?

At the early stage, I rank the founding team first.

The reason is simple: products can pivot, technology can evolve, but the founding team determines whether the company survives and adapts.

The problem being solved is important, of course. But even a strong problem won’t matter if the team cannot execute or lacks conviction.

Technology or the solution is necessary—especially in AI. But at an early stage, technology alone is not enough without the right team and mindset behind it.

Entrepreneurship is abstract and uncertain. What I look for is whether the team truly understands what they’re doing and whether they’re prepared for a long-term challenge.

3. What is the single strongest signal that makes you want to keep digging into a project?

The strongest signal is genuine conviction from the founder.

I want to understand why you’re here and why you care about this problem. I want to see whether you’ve thought deeply about the product and whether your motivation is internal rather than external.

If I feel clarity and a strong sense of purpose from the founder, I’m much more willing to continue exploring the opportunity.

4. Could you briefly introduce yourself and what you focus on as a VC today?

I’m still a relatively novice VC investor.

I graduated from college in 2022, and over the past three and a half years, I worked in Africa and the Middle East. During that time, I invested on behalf of a global company, working within the strategy, venture, and investment arm of a corporate venture capital setup.

I returned to China at the end of last year and joined a venture capital firm around mid-November, so it’s been less than six months in this role.

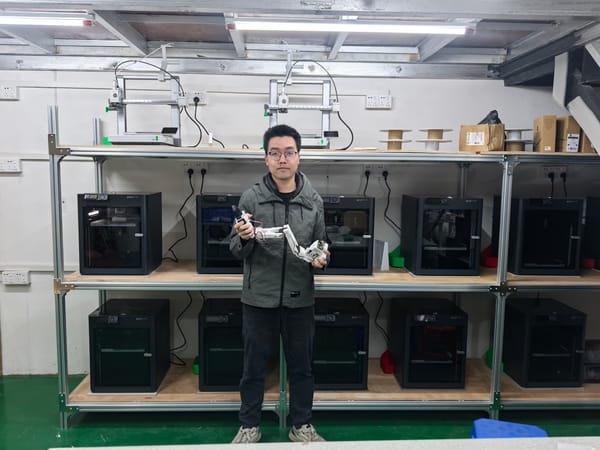

Today, I invest in AI software and consumer electronics / AI-powered hardware, mostly in China or with Asian founders building for global markets.

That’s also why I split my time frequently between Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen. Many software companies are in Beijing, while consumer electronics and hardware companies are concentrated in Shenzhen.

I also spend time between China and the United States, especially Silicon Valley. There are founders who grew up there, studied there, or worked there, and now want to combine their understanding of North American or European markets with Asia’s efficient supply chain to build something global.

5. What kinds of consumer AI–related projects are you seeing most often and which ones actually excite investors?

It’s a very interesting time for VCs. We’re seeing a wave of impressive founders coming from companies like Google, Apple, Amazon, ByteDance, and Tesla, deciding to start their own companies. There’s a wide range of software and hardware projects, some of them are things I personally never imagined people would build.

On the software side, one major category is AI social apps. Founders are reimagining how AI might reshape interpersonal interaction, job hunting, dating, making friends, and communication in general, once AI becomes a variable inside social behavior.

But social apps are also extremely difficult to build.

We also see many productivity tools, especially targeting what people call OPC—one-person companies. AI can dramatically increase the efficiency of an individual coder or artist, so productivity products are a major theme.

On the hardware side, it feels like AI could reshape almost everything in daily life from laptops to personal assistants. Founders are imagining AI rebuilding many of the tools we interact with every day.

What excites investors isn’t AI as a label. It’s whether the product direction makes sense and translates into real usage, especially when founders can connect the technology to a strong consumer experience.

6. Which consumer AI categories do founders most overestimate?

Investors currently have strong appetite for almost anything AI-related, it often comes down to individual taste. If you pitch the right person, you can find funding.

Personally, I’m more cautious about products that sit too close to what large internet platforms can already do.

In software especially, ByteDance can release something overnight that’s ten times better than what a two-person team is building. Some founders are also building features very close to what Gemini already includes in student or bundled plans. If startups try to charge $10–15 per month for something similar, they risk being squeezed by large platforms offering one-stop solutions.

Founders increasingly understand they need to know the capabilities and boundaries of tech giants and avoid building too close to their core.

Hardware is different. Hardware behaves more like consumer goods. AI agents may disrupt SaaS, but hardware is closer to consumer electronics and consumer branding. In many cases, it’s a consumer brand first, and AI-powered hardware second.

For consumer products, opportunities continue across generations. Each generation grows up with different devices and ways of entertaining, learning, and communicating. The opportunity remains; the question is which startups can integrate AI software effectively into hardware and supply chain realities.

7. What are the biggest differences when evaluating AI hardware versus AI software at an early stage?

The moat functions very differently.

There are also different types of AI hardware. For example, in industries like 3D printing, being an early mover can create meaningful advantage. But if you’re building something like an AI camera or AI recording device, you’re entering a space with a very mature supply chain in Shenzhen. In that case, hardware itself is not the moat, the moat lies in the AI software or agent layer built on top.

With AI software and agents, the issue is often the lack of moat. Open-source solutions appear quickly on GitHub, and similar tools can be replicated rapidly.

So for consumer software and agents, you need a highly niche and accurate entry point, true product market fit and a strong ability to tell your story. When code moats weaken, trust becomes the moat. Why should users trust your team and your product?

That’s where brand and storytelling matter more than people expect.

We’ve seen examples like Manus. Many products try to imitate what it does, but it built advantage through strong consumer experience, a clear early positioning, and effective brand storytelling as a first mover.

8. What kinds of founding teams do you personally trust more?

I trust teams with clear ownership and complementary strengths, teams that can genuinely connect technology to product.

In AI, technical ability matters, but product instinct matters just as much. The best founders identify pain points users may not even articulate clearly, and then express those needs through the product.

I also look at whether founders understand how competitive and fast-moving this market is and whether they’re building for the long term, not just chasing a short-term trend.

9. How would you describe the founder mindset in Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen?

Interestingly, I don’t see a huge difference in mindset.

You do see different founder profiles shaped by the environment, more software and AI agents in Beijing, more hardware and consumer electronics in Shenzhen.

But everyone recognizes the importance of AI. Founders are learning aggressively and absorbing information from the global market, not just China. They’re tracking GitHub, open-source models, and global innovation, not only ByteDance, DeepSeek, or Kimi.

In that sense, the mindset is quite similar.

The anxiety level is also similar. In Shenzhen, your neighbor could become your competitor overnight. In Beijing, you might discover a GitHub repo or a release from ByteDance, Gemini, or Facebook, building exactly what you had in mind.

It feels like the best of times and the worst of times for founders.

10. What misunderstandings do overseas founders have when approaching Chinese VCs?

Frankly, we don’t get approached by foreign founders very often, partly due to geopolitical dynamics.

It’s true that Silicon Valley VCs often give more generous valuations for AI startups. I do speak with founders raising in both China and Silicon Valley.

One common misunderstanding is assuming our capital is political. I don’t think that’s the right framing.

We’re in an era of deglobalization, but there’s still respect for innovation and entrepreneurship that transcends politics. I see investors in Silicon Valley and Shanghai sharing similar mindsets and I see this even more strongly among founders.

Founders are trying to build global products, software, hardware, agents, consumer electronics for a global audience, as day-one global teams. On a macro level, the world may be separating. On a micro level inside tech, people are bridging gaps with code and products.

Products tell the founder’s vision.

Personally, I’m open to conversations with founders anywhere in the world who want to build global companies. AI products should be global.

11. If a founder plans to reach out to VCs soon, what should they fix first?

I would summarize it in three questions: why now, why this, and why you.

“Why now”. Saying AI is a paradigm shift is not enough. You need to show your niche entry point, your product-market fit, and your ability to scale quickly with AI.

Investors want to see that you’re not only thinking about the next three months. You need to explain how your team, product, and strategy will evolve over the next 12 months and the next three years.

“Why this”. What pain point are you addressing, why does it matter, and why would users pay for it? Some needs aren’t obvious; strong product founders identify and articulate them through their product.

And “why you”. This isn’t always asked directly, but we assess it through conversation and storytelling. It’s critical.

So timing, product, and team: why now, why this, why you. These are the core questions every founder should think through.