Before the Robot Becomes a Product

This is not a startup announcement or a success story. It’s an early-stage exploration of how hardware ideas form, where they tend to break down, and how places like Shenzhen shape what happens both before and after companies exist.

The conversation didn’t start with a startup idea.

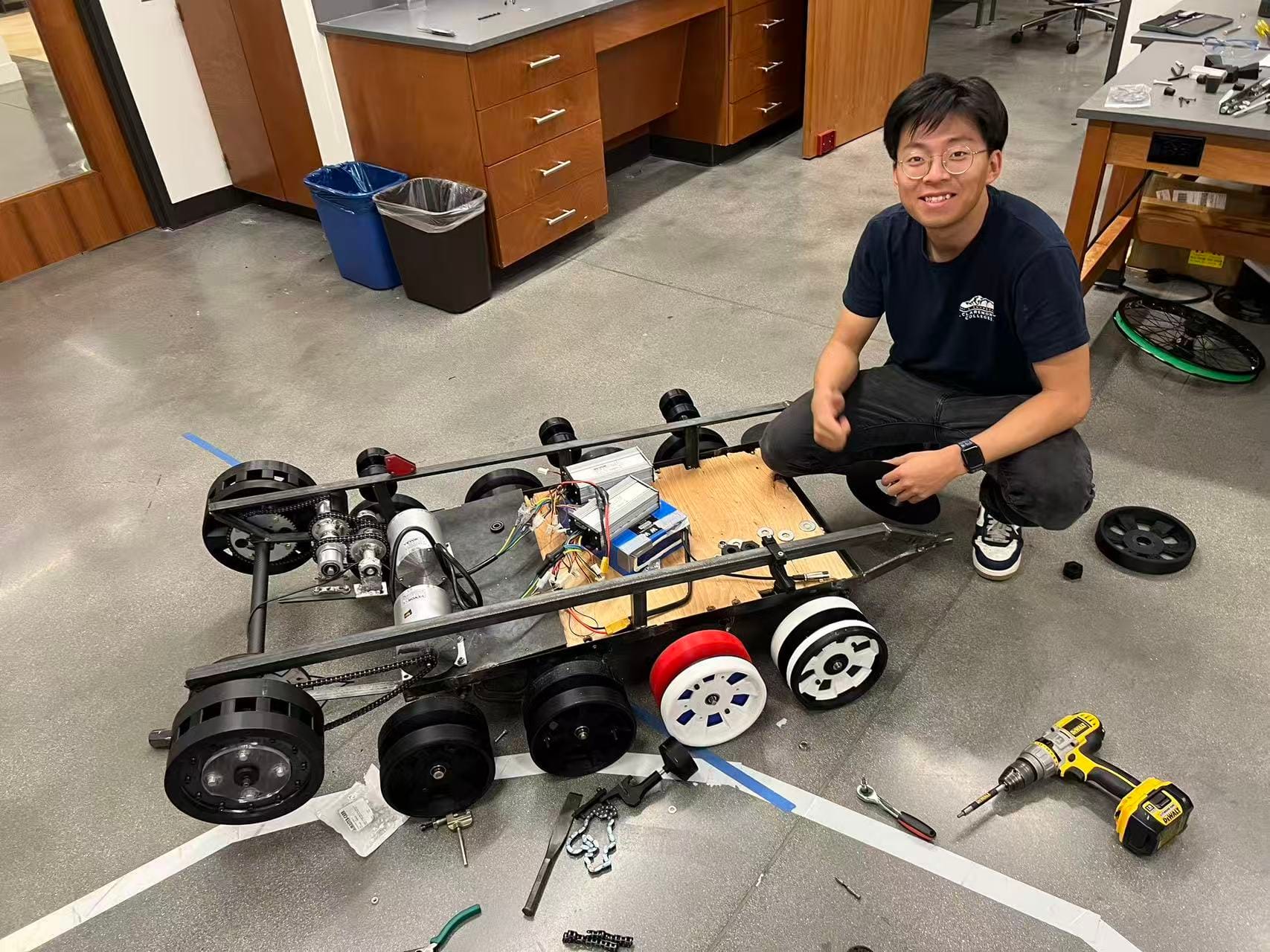

It started with something more ordinary: Donny and his friends were trying to build robots at school, and everything felt slower than it should. Not because the code was wrong. Not because the designs were impossible. But because small, practical things were hard to get.

- A motor that worked well enough.

- A part that didn’t cost thousands of dollars.

- A way to test something quickly without committing months of time.

At first, it felt like a student problem. Hardware is expensive. Budgets are limited. That’s normal.

But the more Donny built, the more he noticed a pattern. Projects weren’t failing because the technology didn’t work. They were stalling because teams couldn’t move past the first version.

The gap wasn’t between “idea” and “prototype.”

It was between “this works” and “this can actually be made.”

That gap started to matter more to him than the robots themselves.

Building Wasn’t the Hard Part

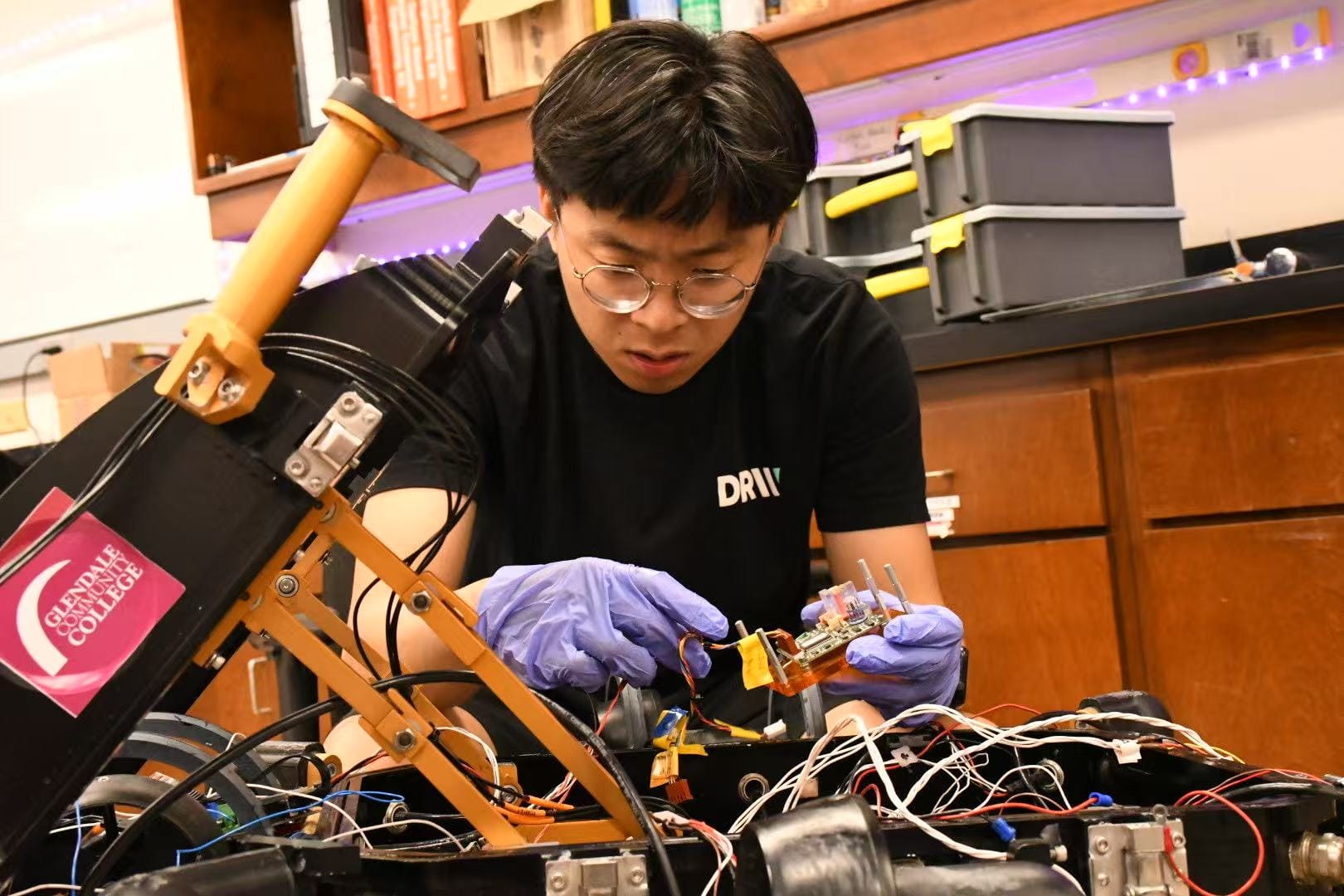

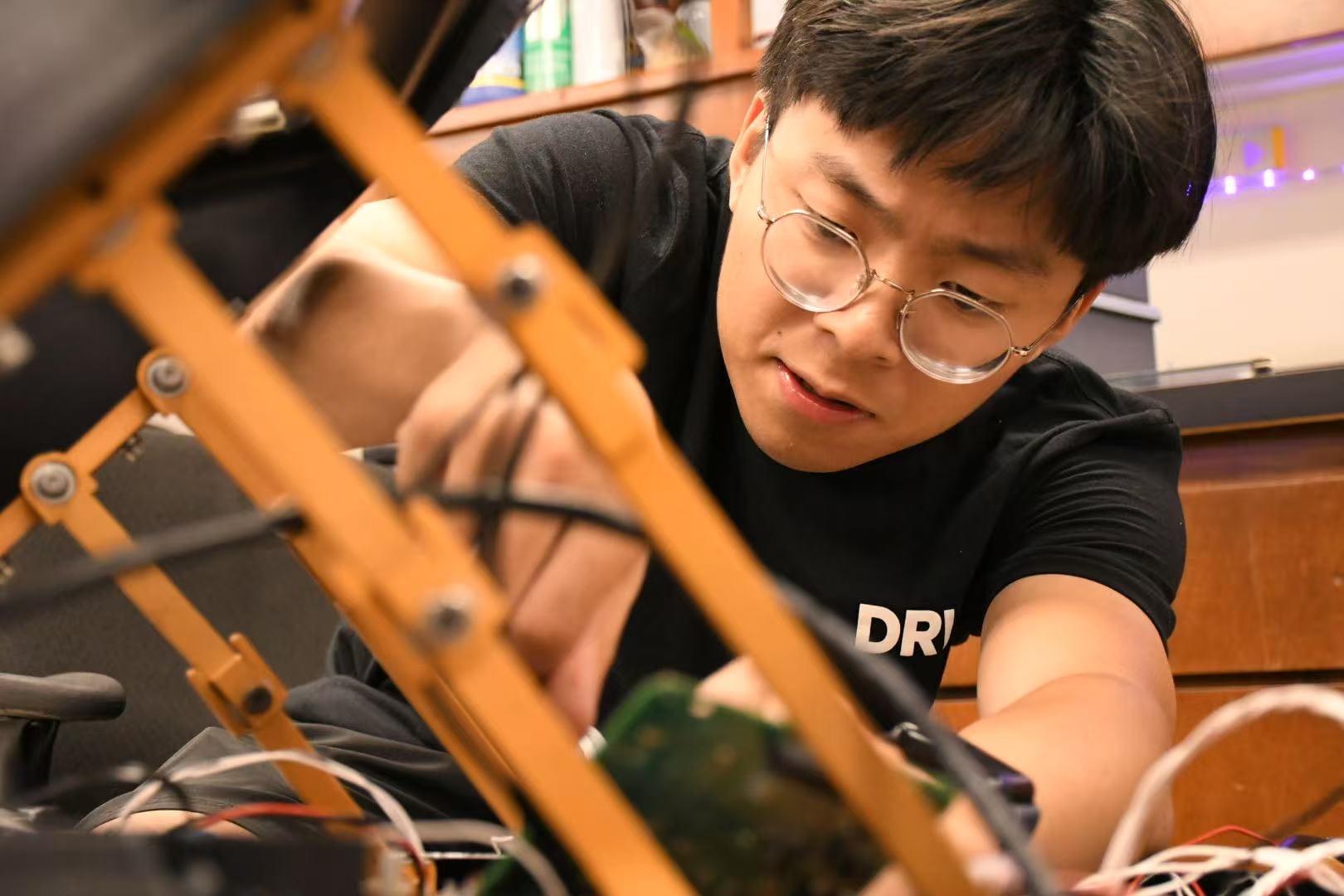

Donny studies physics and aerospace in the US. Outside of class, he spends most of his time building robots with friends, humanoid robots, small experimental machines, whatever they can realistically attempt.

The first version usually isn’t the problem. You can 3D print parts, order components online, make things fit well enough to test an idea. At that stage, the system works.

The trouble starts when you want to build the next version.

- A part breaks and needs replacing.

- Something needs to be customized.

- A component isn’t available unless you order thousands.

Certain motor parts, for example, are hard to get in the US without committing to large volumes. The same parts might take a few days in Shenzhen. In the US, they can take weeks. Or they’re not accessible at all.

For student teams, that delay is often where projects quietly end. Not because the idea failed, but because momentum disappeared.

“You don’t need aerospace-level precision for most robots,” Donny said. “But the system here is built around that. Everything assumes high cost and long timelines.”

The mismatch creates friction right when speed matters most.

It Wasn’t Just About Cost

It’s easy to explain this as a pricing issue. Manufacturing in China is cheaper. That’s the simple story.

But Donny kept noticing something else. In the US, manufacturing is fragmented. One shop does CNC. Another does molds. Another handles electronics. They’re often expensive, far apart, and not set up for small teams.

In Shenzhen, those boundaries feel looser.

Factories talk to each other. Many handle several steps in-house. And just as importantly, they’re willing to work with early-stage teams, because today’s small order could turn into a long-term relationship.

That changes how things move.

Iteration cycles shrink. Feedback comes faster. You’re not just buying parts; you’re learning what can and can’t be done.

When Donny talked to early hardware teams in the US, he heard the same thing repeatedly. Prototyping locally was fine. But once teams needed small batches or real-world testing, they had to come to China.

Not because they wanted to move everything overseas.

But because the local system didn’t support that stage.

That shifted how he framed the problem.

It wasn’t about where to manufacture.

It was about which stage each place actually supports.

When a Frustration Turns Into a Question

At some point, the frustration became curiosity.

If the US struggles with the “one to ten” stage, early batches, testing with users, fast iteration, what would it take to make that easier?

Not a massive factory. Not a big bet. Something smaller and more experimental.

Donny began sketching an idea: a small manufacturing lab inside a co-working space. A place where hardware teams could build, test, and iterate without committing to full-scale production.

The focus wasn’t on owning machines. It was on access and speed.

Instead of every team figuring out manufacturing alone, they could share infrastructure. Instead of waiting months for tooling, they could try short-run approaches. Instead of guessing what might scale, they could test assumptions early.

It wasn’t a finished plan. More like a working question.

If you reduce friction early enough, do more hardware ideas survive long enough to matter?

Why Small Matters More Than Big

One assumption Donny kept running into was that manufacturing automatically means heavy investment.

When people hear “factory,” they imagine large buildings, expensive equipment, and slow returns. He doesn’t disagree with that history. But he thinks it misses the early stage.

Early hardware teams don’t need scale. They need speed.

They’re not optimizing for margin. They’re trying to learn. A slightly higher cost doesn’t matter if it saves weeks. Perfect tooling doesn’t matter if you’re making a hundred units.

That’s where the idea of a small, shared lab comes from. Not to replace Shenzhen, and not to recreate it, but to support the part that usually breaks down first.

Short runs.

Fast feedback.

People who understand how designs turn into physical objects.

Less about production. More about learning through building.

Going to Shenzhen to Check His Assumptions

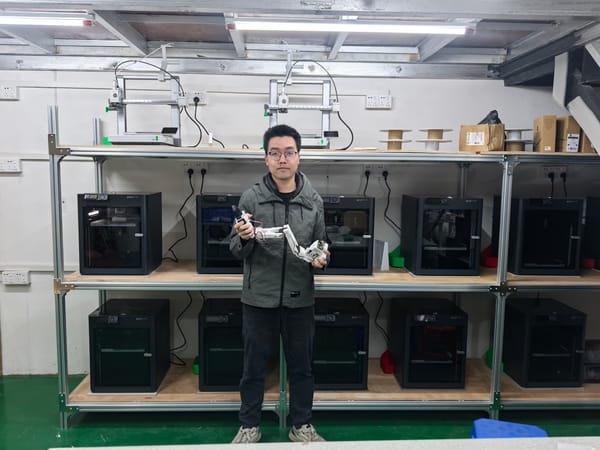

Donny’s winter trip to Shenzhen wasn’t about deals or sourcing. It was about seeing whether his thinking held up.

He tried building a simple project, just to compare the experience. What surprised him was that the act of building wasn’t dramatically faster. A skilled builder can move quickly anywhere.

The difference showed up later.

- When you want the tenth version.

- When you need hundreds of parts.

- When testing, assembly, and quality start to matter.

In Shenzhen, those steps are connected. A single factory might handle molds, assembly, electronics, even shipping. And they care about whether the product works, because they’re thinking long-term.

This is often misunderstood from the outside. Hardware isn’t just design plus assembly. Testing and manufacturability shape whether a product survives at all.

Shenzhen’s advantage isn’t just speed. It’s continuity.

The Idea Starts to Take Shape

At this point, Donny and his team are taking these questions seriously enough to explore them as a startup, and they’re raising early funding around it.

The physical lab is one part of the idea. The other is software, which he describes in very practical terms. He talks about tools that help teams move from early designs to something that can actually be manufactured, understand what kind of production they need at different stages, and connect with the right manufacturing partners as they scale.

It’s meant to work alongside the space, not replace the hands-on process. Like everything else at this stage, it’s still being figured out.

Some Assumptions Started to Shift

Spending time on the ground also changed how Donny thought about Chinese companies.

From far away, they’re often described as fast imitators. What he saw was something more demanding. Many teams are under constant pressure to improve products while lowering costs. Copying isn’t enough to survive.

That pressure forces discipline. Designs account for manufacturing early. Testing is taken seriously. Efficiency isn’t optional.

This wasn’t about comparison or judgment. It was about noticing what systems reward, and what they quietly discourage.

In software, it’s often enough for something to work once.

In hardware, reliability decides everything.

No Conclusions Yet

There’s no finished company here. No polished model. No certainty that a mini factory lab inside a co-working space is the right answer.

What exists is a line of thinking shaped by building, talking to other teams, and watching where things consistently slow down.

For now, Donny’s goal isn’t scale. It’s to help a small number of teams move past early bottlenecks without losing momentum and to learn from that process.

If it works, it suggests something worth paying attention to.

If it doesn’t, the learning still matters.

Because before hardware becomes an industry, it begins as a question:

And understanding why the answer is often “not yet” is where the work really starts.