Before the Company Exists: Samuel and the Work That Comes First

Since last year, Samuel has been moving between the US and Shenzhen while building early hardware projects. This story follows what shapes hardware ideas before a company exists — cost, iteration, and the decision to show up in person.

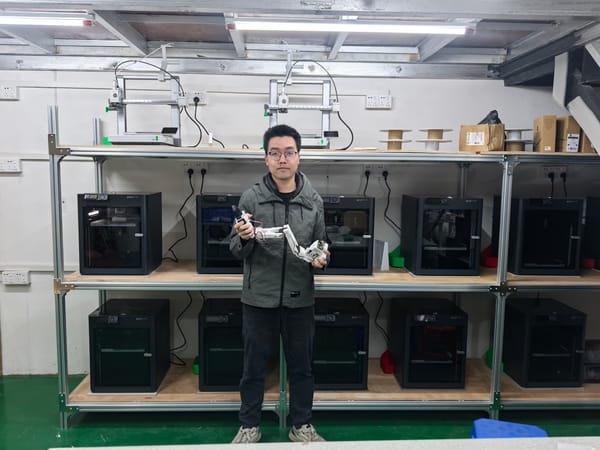

Samuel has been going back and forth between the United States and Shenzhen since last year.

He’s a computer engineering student at Northwestern University. He’s still studying, interning, and building on the side. There isn’t a finished company at the center of his story yet.

What keeps pulling him back isn’t scale or ambition in the abstract. It’s a desire to understand how hardware ideas actually become real before decisions get locked in, and before a company exists.

This is a story about that stage.

Building early, and learning where costs come from

Samuel started building early, largely because he wanted to experiment.

While still in high school, he was working on a project that required specific electronic tubes. Buying them in the US was expensive, often out of reach for a student project. To make it workable, he began sourcing tubes from Russia, where prices were lower.

That came with its own friction. Shipping took time. Logistics were complicated. DHL costs added up quickly. A single order could take weeks to arrive, and the total cost was never just the parts themselves.

Around that time, Samuel set up something he called the Electric Tube Company.

The purpose wasn’t to build a startup. He resold tubes in the US to fund future purchases, so he could continue experimenting without stopping every time costs piled up. It was a practical loop: buy, resell, reinvest, repeat.

Electric Tube Company still exists. In this story, it matters mainly as context. It shows how early on, Samuel was already dealing with sourcing, pricing, and logistics, long before anything resembled a company.

What stayed with him wasn’t the business side of it, but the lesson: even small hardware experiments are shaped by cost and access much earlier than most people expect.

When experimentation becomes slow

As Samuel continued studying computer engineering in the US, he kept building alongside school. Circuits. Early hardware experiments. Projects that were exploratory rather than directional.

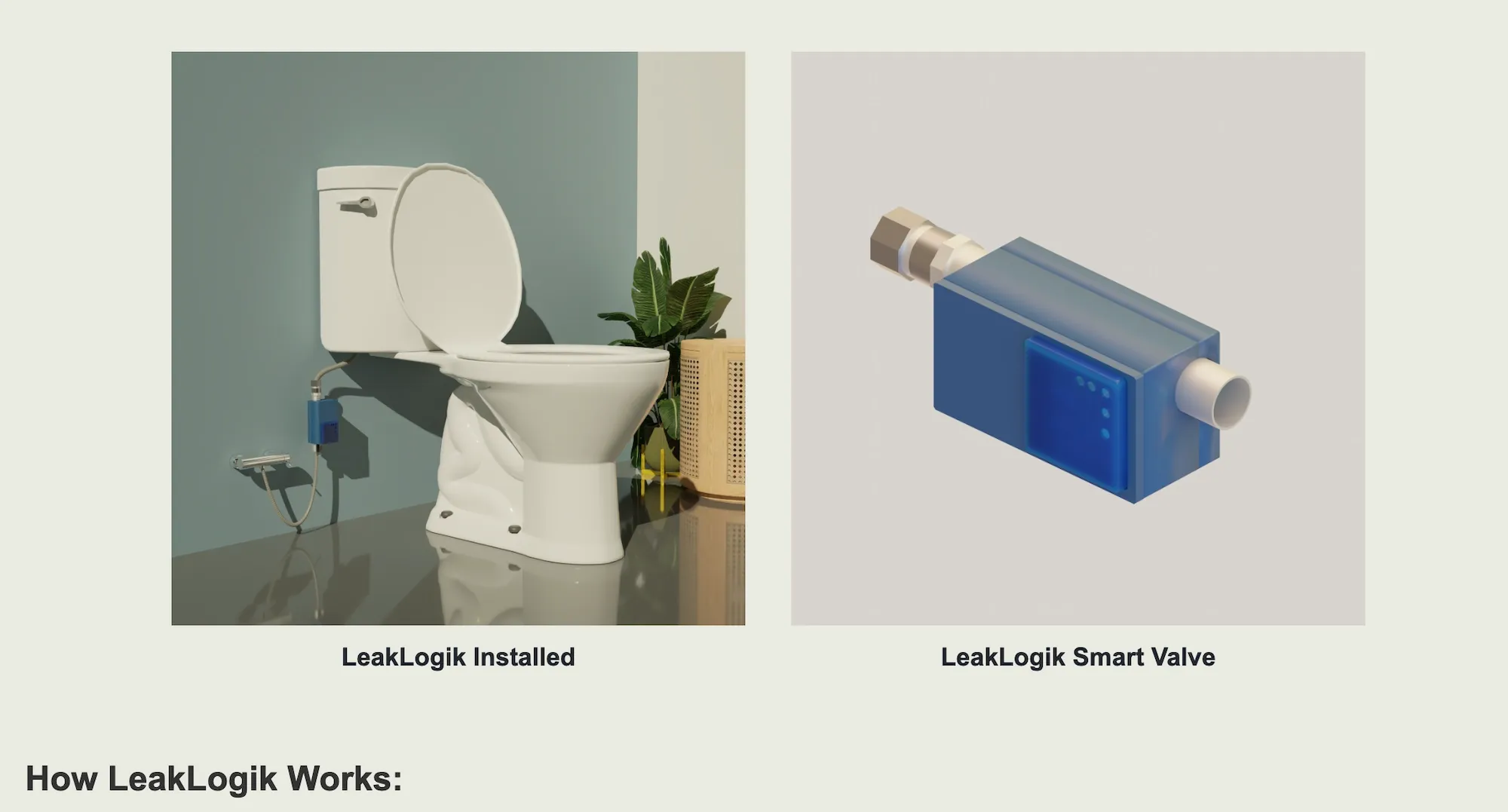

More recently, this has included LeakLogik, a project he’s still working on while studying and interning. This time, it’s a project he’s treating more seriously, with the possibility that it could become a business.

Over time, a pattern became clear.

Early hardware experimentation involved a lot of waiting. Parts often took weeks to arrive. Custom components were costly. International sourcing added delays and uncertainty. Shipping fees could quickly take up a large part of a small budget.

Each iteration required planning and patience.

“You end up thinking a lot before building,” Samuel said. Not because thinking is the goal, but because building takes commitment.

For students or individuals working alone, this changes how experimentation feels. Ideas don’t disappear, but they slow down. Some never move beyond planning.

That tension is what kept drawing Samuel back to Shenzhen.

What he noticed in Shenzhen

Samuel’s trips to Shenzhen weren’t driven by a plan to manufacture or scale. They were exploratory.

He spent time in markets, factories, workshops, and shared working spaces. He talked to suppliers. He asked practical questions. What could be changed easily? What usually caused delays? What assumptions stopped holding up once something became physical?

One thing stood out: how iteration fit into everyday activity.

If a part didn’t work, alternatives were often nearby. If one person couldn’t help, they recommended someone else. People were used to early-stage questions and incomplete ideas. Feedback happened quickly, often face to face.

This wasn’t about rushing. It was about proximity between parts, people, and knowledge.

That proximity made it easier to try things, adjust them, and try again without long pauses in between.

An environment shaped around making things

What Samuel was responding to wasn’t just speed or price.

It was the environment.

Factories were familiar with early-stage uncertainty. Suppliers expected questions that didn’t yet have fixed answers. Conversations about tooling or feasibility didn’t automatically lock decisions in place.

Iteration felt like part of the process rather than an interruption.

Instead of treating each prototype as something that needed to be right, Samuel could treat it as something that needed to be informative.

That difference mattered.

People, not just processes

Supply chains were only part of what kept Samuel returning.

The other part was people.

Being in Shenzhen meant meeting suppliers, builders, and engineers in person. Not just for transactions, but through daily interaction. Over repeated visits, relationships formed naturally.

When people recognized him and saw that he kept coming back, conversations changed. Context was shared more openly. Introductions happened more easily. Help felt less formal.

Samuel also spent time in shared working spaces and local incubators like InnoX, working alongside other technically curious builders. These spaces weren’t organized around outcomes. They functioned as places to build, observe, and exchange ideas.

For someone still figuring out what to work on next, that environment mattered.

Still exploring

Samuel continues to work on LeakLogik while staying open to other ideas. He pays attention to problems he encounters, tools he uses, and constraints he keeps running into.

There isn’t a single direction yet. And that’s intentional.

What he’s gaining at this stage isn’t a company or a clear path forward. It’s a clearer sense of where hardware ideas tend to slow down, and what kinds of environments make experimentation workable.

Shenzhen, in this story, isn’t a strategy or a promise.

It’s a place where early exploration can continue without pressure to resolve.

Samuel is still in that phase.

And that’s where this story stays.